Grafton Architects, selected as curators by the president of the Venice Biennial Paolo Baratta, are among those authors with the ability to provoke a different yet never mainstream look at the urgent issues that characterize our world.

The call by the Irish Yvonne Farrel and Shelley McNamara, aka Grafton Architects, is typical of this approach and has aroused a good deal of curiosity about what will be presented in the coming months. Platform met them beforehand to hear them explain their vision and work philosophy.

LM | The key title of Platform is “engaging” as a sense of a direct participation in the life of a community to the quality of the place where one lives and I found it very sympathetic with your Freespace Manifesto. You talk about generosity and humanity, which should be the goals of architecture for the next decades in relation to the perception of architecture among common people.

G | It’s important to remind ourselves that architecture is a very complex discipline. It’s a difficult job and there are many things to consider simultaneously. We ask ourselves: “What is our role? What are we trying to do?”. The more we work, the more we realize that the issue of what we give back to society is very important; of course, we deal with clients, with money, with function.

Architects interrogate the needs of a client for each project. Architects cannot make a good building without interrogating these requirements in a detailed way. But, as architects, we have to be able to stand back and see the overall scheme of things, in order to be able to ask questions “What is the meaning of architecture in relation to society; what is the bigger picture?” We need to zoom in very close to the fundamental requirements. But it is also important that we zoom out to see the larger picture. The longer we work, the more we realize, that sometimes what is ‘not requested’ is the very thing that makes the project really special. That ‘not requested’ aspect can come out of the agenda of the architect. To explain what we mean, in our Freespace Manifesto, we refer specifically to a wonderful project in Milan, on Via Quadronno, by architects Mangiarotti and Morassutti.

What struck us very forcibly when we visited it, was that the building allows a person to feel a different agenda – a different value system is present its architecture.

Somehow, this kind of value system is less common in contemporary buildings, where you get the real sense that the architects are thinking about the human being as the user. Thinking like this, is the first point of departure, not as a token. The building is not narcissistic.

The building form is very strong; it’s a little tower; it makes a statement, but it also seems to reach outwards to society, not inwards to the persona of the architect. This relates to a humanistic content, which was present from the very start in the agenda of the architects. This is an example of how we felt this idea of generosity and asked ourselves: “What is the extra? What is the additional component that the architect brings to the project and connects with society?”. This is an important ingredient which we would like to focus on for the Architecture Biennale – this additional component, sometimes very subtle, sometimes very strong, but which actually has to be there in your pencil, in a way, from the moment you start to think about the design. What are we trying to do? What is our role in society? You’re asking about generosity and humanity. Architecture has such an enormous cultural component that we want to prise it open and use words that are accessible, not only within the professional world but by the general public. The architect is involved in the business of construction and even though the pressures on the profession are enormous, when the project is finally complete, all the pressures evaporate into thin air and the project, the built form exists in its own right. It is important to find the energy, a protection system for the very things that are at the core of architecture. That’s what we are searching for in the Manifesto. We discovered as we thought about it, that a Manifesto could be a list of aspirations, which could be like a litany – written down, so that they could be mulled over and hopefully make complex things more clear to a wider audience. We would love that the Manifesto would be something that a non-architect would find useful in the future, as a yardstick or as a measure, so that people would to be able to search for the components of generosity and humanity in projects in that the Manifesto could be used as a yardstick to confront and evaluate.

LM | I think that “Freespace” is a subtle and straightforward conceptual shift in relation to the past century, where everything was related to boxing everything up. Today considering the centrality of what you call “Freespace” is instead the complete opposite and represents the fact that people are looking for spaces which allow different kinds of experiences. We are facing a completely different historical phase, where free spaces are probably the stages where the contemporary community can perform and find a possibility to express.

G | What you’re saying is really a challenging ideal of the future. What kind of communities will we have? Where people will meet one another? This is especially important in the contemporary world of cyber communication. Architecture’s important role is that we are held by building. It is how we are enclosed. We feel that the role of architecture now is more critical than ever before. The impact of built form on what we experience day to day is enormous. One of the things that we love about the Freespace Manifesto is people’s response to ‘The Earth as Client’.

This is an enormous responsibility, not only in terms of the air we breathe but the way we use the Earth’s resources. For example, the issue of how we specify timber or stone for buildings? where does the material come from? how much do we ‘eat up’ of the earth, of the existing resources? We are hoping to make people more aware of what we do as a profession. Every time we specify a particular material, we are effecting a mountain, we are cutting a forest… In our Manifesto we refer to Jørn Utzon, who has made many beautiful projects. We have highlighted the concrete and tiled seat he made at the entrance of his house Can Lis in Majorca, which ‘holds’ the human body perfectly comfortably. At another scale, Utzon’s architecture in the Sidney Opera House represents a society, represents Australia. Architecture has the capacity to span from the intimate and tactile to the representation – to become the symbol of a nation. Architecture is an incredible discipline which spans a huge range of scales.

G/Sh | I’m very interested in the term you used, I think you said something about architecture being boxed in. Recently we were reading an essay dealing with the Vasari corridor in Florence. It was an extraordinary critique on culture and how it is integrated or not integrated into the city. This is a wonderful idea of the Vasari corridor moving from a Palazzo to what was an office building, up a staircase, across the bridge, into a tower in another Palazzo overlooking the gardens. Compare that with the contemporary need to make museums into hermetic boxes, into a very large scale of elements which by their nature, and because of their scale, become isolated and, because of security, become even more isolated! This is architecture becoming more hermetic and defensive! It’s such an interesting point how certain uses are ‘packaged’ and presented. We prefer the idea of things being open, rather than things being closed. Architecture has to have some element of being defensive obviously, because you could be shot or murdered or attacked in a city! Architecture’s role can go beyond fear, money and all those pressures and can find some components, which are generous and open.

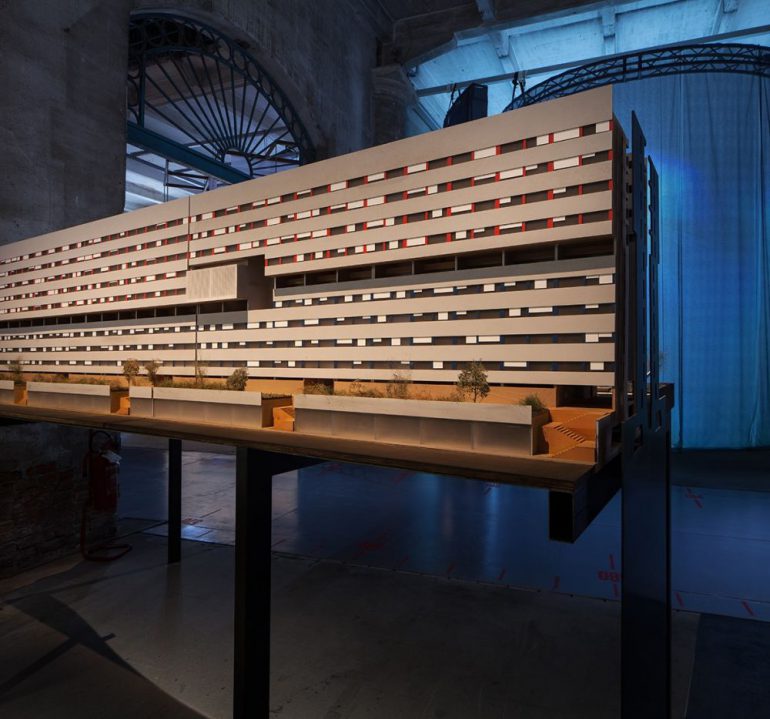

G | When you talk about the future, the integration of structure and landscape can be liberating. We have discovered in some projects, that all you need is 300 mm of soil to allow trees to flourish over time. Architecture and landscape can merge in order to enjoy the pleasure of nature. One of the aspects of the Manifesto encourages planting trees, even though you may not be alive to appreciate them in the future. We would like people to be aware of the passage of Time. As architects, we set up infrastructures for life where we are guessing what the future will be. Architects can make spaces where people can gather. Hopefully, the examples in this year’s Architecture Biennale facilitate change. We are really trying to have a discussion about the things that are achievable – not just about ideas for idea’s sake.

LM | Reading the Manifesto I loved one of the examples you brought in relation to the Medici building in Florence. I was always impressed by the fact that those buildings always have a stone bench on the facade, a place for everybody, which allows people to be welcomed, a generous space for the community. This reflection brings me to another important thing: you have naturally a background as a designer, in a way you’re always trying to match the contents you are talking about into real bodies, spaces and form, which for me is the final result of architecture. So which is the relationship for you, between creating a new agenda of values and the contemporary definition of forms?

G/S | I’m not sure about the new agenda, in a way what we are trying to remember the ancient agendas as well as the future agendas; when you talk about the Medici I mean that’s still a huge lesson to learn. You can have something as defensive as a bank full of money, but you could be generous to the society with something really simple that doesn’t cost a lot of money. I think we’re actually remembering, revisiting past values, which in many ways are much more sophisticated than current values and trying to carry those lessons into the future. For instance, one of the things we have often been questioned about is why are we so interested in heroic architecture It’s not that we have ever said to ourselves that we are interested in heroic architecture or in the monumental. It’s because we visit ancient buildings and we feel wonderful in these spaces, where you can feel the sense of the mass, the forces of gravity, you can feel the materials, you can feel other lives and we thought “How can we make something which can touch that note now?”. When you talk about something new, we are great believers in T. S. Eliot’s definition of time, that it’s about past, present and future held in one sphere and that the new might be a sequel from first century B. C.. We don’t think about time like that. We think that the new fresh is also important. We are not nostalgic about the past because sometimes you see a work, and there are a couple of examples at the Biennale like that, where there is a fresh interpretation of something familiar. That’s always exciting. It’s a fine tuning of something that’s familiar, as well as having another dimension, another reading.

G/Y | What we think that’s really important, Luca, is the issue of dimension. Architecture causes a physical reaction in you as a person. Architecture can make you feel more human. In some places you can actually feel frightened by the architecture because that’s the component it wants to convey. On the other hand, I remember being in Verona in Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio for the first time, the design was so perfect that I ‘heard’ the little stairs calling my name to walk up its beautifully crafted steps! In relation to space in the Biennale, it would be wonderful if people could become more aware that they are human beings of a certain size, in a particular space.

We would like to make people more aware of their physical presence in modern society. There is a tendency in modern life to forget that you are a human being with senses. What’s really interesting for us in curating this enormous exhibition is to encourage people to remember to take time to enjoy, to sit down, or to stand, or to walk and to consider what dimensions are surrounding you; to think that architects respond to humanity at the scale of a beautiful handrail, a beautiful door handle, a bench, a wall. We hope that the Biennale encourages people to think about the large scale infrastructural, global view of humanity, as well as the free gifts of moonlight, sunlight, shadows; to imagine a future where comfort and craft, are linked together with architecture.

LM | What you call the relation between the archaic and the contemporary I think is going to be considered something that is universal; something we perceive everywhere, a kind of natural behaviour of the architectural space which makes us “natural architects” somehow. What you think goes apart from fashion, changes of taste, and brings the architecture to the basics, to something that everybody can understand. I think that today one of the challenges we have is to bring back people to understand architecture as a social value, as something that can heal, help people to be together, to demolish distances, so as a very strong political value which I think is necessary today.

G | You’re talking about the political dimension of architecture, the potential for it to be a socializer, an informed container of society. In our profession as architects, we look for things that allow people to interact with one another, to be aware of each other. Kenneth Frampton says that architects have lost the ability to make spaces which bring people together. I suppose we have used his statement as a provocation. The reason for the situation being like this has very little to do with architects themselves. It is because of the fact that architects have in reality very little power. There is something which is important for us to discuss regarding our choice of projects for the Architecture Biennale 2018. It is the matter of scale. In fact, a variety of scales… We believe that both large and small projects affect society. It is important to ask questions: How can a very small project affect the big problems of society; how can it repair the wrongs of society? You would think that this is not possible at one level, but…on the other hand, it is amazing that sometimes small projects can totally transform a situation. Thinking in a very open way about a small project can re-form the way one might address a much larger project and visa versa. There is probably an inherent problem in the way some master plans are thought about in the abstract, where the tactile experience of the individual is not considered at the same time as considering a strategy for traffic or infrastructure. Bringing together large and small scales simultaneously, is really important. We are quite optimistic that there are architects working with sincerity, with passion and skill, placing value on society. The issue of dimension is fundamental to the discipline of architecture. We have to be careful to remember scale. The phenomenon of architecture involves the judgment of measure.

LM | You put teaching as a central element into your Architecture Biennale which I think is very important because the university is probably the best place to experiment and to create a different kind of awareness and consciousness about the role of architecture for the next few years. I think it’s a fundamental place where to learn how to do and train your soul, your eyes and your ears.

G | I think it was Josef Albers who asked what is the difference between teaching and learning, and that’s something we are very conscious of. I think it has to do with University, but also has to do with how teaching feeds factors because we all know that if we are stuck in an office with a problem and we go into an atelier, a studio, we have to become a different person, where we come out renewed and invigorated. It’s a two-way thing! We think it’s really important because university is like a laboratory of imagination and the student and the teacher can imagine together, free of many of the constraints of the so-called reality. This a wonderful place to be, to have that freedom. In the Biennale, we have chosen to focus on the relationship between practice and the practice work of teaching. It’s not that we don’t value academics. We do know the essential value of a history and theory course, for example, is an enormous resource. In the Biennale, we are focusing on the connection between the maker of buildings and the person who has not yet made buildings. This affects the way one thinks about construction, materials, and equips a student to deal with reality. The university is a place where you can have lots of ideas, but it’s not real. The study of architecture has to equip the student to deal with resources, with reality. It deals with the continuity of values, with cross-fertilization between teachers with colleagues, teachers with the students and, as you say, it’s a place of experimentation and challenge. Many of the participants in this year’s Biennale are also teachers, and we stress the point that colleagues are really very important in the culture of architecture. It’s difficult being a practicing architect. It is especially good to be in the company of other architects who are, like you, trying to strip away the enormous effort of making in order to make it accessible to young people, who are curious about the profession. Schools of architecture are places of hope, that’s how things are grown. Returning to the discussion of how people establish their own values, which is not about a particular style. It is about how you grow an attitude to Life.